Scroll to:

Characteristics and outcomes in outpatients with heart failure in Russia: results of a large-scale prospective observational multicenter registry study PRIORITY-HF

https://doi.org/10.15829/1560-4071-2025-6516

EDN: DZOXMG

Abstract

Aim. Geographic heterogeneity of phenotypes and prognosis in heart failure (HF) highlights the need for region-specific data. The aim of the study was to evaluate characteristics, therapy, and 1-year outcomes in a Russian large representative cohort of outpatients with HF.

Material and methods. PRIORITY-HF is a prospective, observational, multicenter registry study. From 2020 to 2022, outpatients diagnosed with HF aged 18 years and older were included in 50 regions of the Russian Federation.

Results. The study included 19,981 patients with HF (mean age 64.9 years; 63.5% men). HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) was diagnosed in 34.9% of patients, while HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) — in 24.7%, and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) — in 40.4%. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (89.0%), coronary artery disease (73.4%), obesity (45.2%), chronic kidney disease (44.7%), and atrial fibrillation/flutter (42.5%).

There was high prescription rate of individual classes of recommended HF therapy as follows: 92% of patients received renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, 86% — beta-blockers, 72% — mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and 40% — sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, but only 46.6% of patients with HFrEF received quadruple therapy.

After 12 months, all-cause mortality was 5.2% in the overall group (HFrEF: 8.1%; HFmrEF: 4.6%; HFpEF: 3.1%), while cumulative HF-related hospitalization rate — 6.3% (HFrEF: 10.4%; HFmrEF: 6.2%; HFpEF: 2.9%).

Conclusion. The obtained data indicate a relatively young age of patients with HF in Russia with a high level of comorbidities and suboptimal therapy, especially in HFrEF. With relatively low mortality and rehospitalization rates, significant differences between the EF subgroups were revealed, which emphasizes the need for targeted interventions to improve the quality of care and prognosis.

For citations:

Shlyakhto E.V., Belenkov Yu.N., Boytsov S.A., Villevalde S.V., Galyavich A.S., Glezer M.G., Zvartau N.E., Kobalava Zh.D., Lopatin Yu.M., Mareev V.Yu., Tereshchenko S.N., Fomin I.V., Barbarash O.L., Vinogradova N.G., Duplyakov D.V., Zhirov I.V., Kosmacheva E.D., Nevzorova V.A., Reitblat O.M., Soloveva A.E., Zorina E.A. Characteristics and outcomes in outpatients with heart failure in Russia: results of a large-scale prospective observational multicenter registry study PRIORITY-HF. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2025;30(11S):6516. https://doi.org/10.15829/1560-4071-2025-6516. EDN: DZOXMG

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) presents a significant challenge to healthcare systems worldwide due to its increasing prevalence, frequent hospital readmissions, and detrimental impact on quality of life and survival [1-5]. Despite the advancements in guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), which has been shown to reduce the risk of mortality by up to two-fold [6], several studies have indicated a rising trend in HF-related deaths [7][8].

Large registry studies are instrumental in assessing real-world HF management and patient outcomes, as well as understanding and identifying opportunities to overcome the individual, organizational, and community barriers for implementation of evidence-based strategies into routine clinical care [1]. Previous global studies and HF registries have demonstrated considerable heterogeneity in patient characteristics and clinical outcomes across individual studies, countries, and regions [9-15]. For instance, data from the European HF registry encompassing 21 European and/or Mediterranean countries reported 1-year mortality rates for chronic HF ranging from 6.9% to 15.6%, with hospitalization rates varying between 4.0% and 21.3% [12].

In the Russian Federation, large-scale HF studies are limited, and comprehensive data on HF are scarce [16-18], largely due to the absence of a centralized system for collecting statistical data on HF. The specially designed EPOCH-CHF study, one of the few epidemiological studies on chronic HF, was conducted in only a few central regions of the country in advance of currently established HF diagnostic criteria and recommended classes of GDMT [16].

To address this gap, the PRIORITY-HF study, a prospective, observational, multicentre registry, was designed to study a large representative cohort of patients with chronic HF in the Russian Federation. The primary objectives of the study were: (1) to characterize the baseline clinical and demographic profiles of HF outpatients, and (2) to assess the routine therapy for treatment of HF and physician compliance with current national clinical guidelines for management HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

Material and methods

Study design and patient population. RIORITY-HF (NCT04709263) was a nationwide, prospective, observational, multicentre cohort study evaluating routine clinical practices in the management of HF outpatients across Russia. The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline (Supplemental Table 1) [19]. The trial design has been previously reported [20]. In brief, the study consecutively enrolled HF outpatients aged 18 years and older who were under the care of general practitioners or ambulatory cardiologists. HF diagnosis was based on the 2020 National clinical practice guidelines [21]. Initially increased levels of natriuretic peptides (NP) were required as an eligibility criterion for HF with mildly reduced (HFmrEF) or preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). However, given the feasibility challenges in assessing NPs, the protocol was amended permitting patient enrollment based on definitive HF diagnosis established on alternative objective criteria.

To ensure a representative patient sample, 141 study sites were strategically selected across 50 regions spanning eight federal districts, considering Russia’s geographical and ethnic diversity. Sites were selected taking into account the outpatient HF management practices, healthcare facility levels and geographic location. The recruitment period extended from 21 December 2020 to 29 December 2022.

Comprehensive patient data, including demographics, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) measurements, HF classification, comorbidities, laboratory parameters, treatment history, vaccination status, intracardiac device implantation, surgical history, and clinical outcomes, were documented by physicians using a structured electronic case report form (eCRF). Data quality and integrity were ensured through programmed validation checks within the eCRF, supplemented by external monitoring and verification conducted by specialists from an independent contract research organization.

The study protocol was approved by the independent local ethics committees of all participating centers before the enrollment of study participants. The study was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. The data that support the study findings are available from the study sponsor on reasonable request.

Follow-up period and assessment of clinical outcomes. Patients were followed up by physicians in accordance with the routine clinical practice. After the baseline assessment at visit 1, follow-up visits were scheduled at approximately 6 and 12 months (visit 2 and visit 3, respectively). Data on the changes in clinical status, LVEF, laboratory parameters, treatment, and major clinical events (death, first and recurrent hospitalizations, causes of hospitalizations, surgeries, other adverse cardiovascular events, and newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus or malignancies) during prospective follow-up were recorded in the eCRF. If required, additional information was obtained through patient relatives or electronic medical records. Causes of death and hospitalization were determined by the treating physician. In cases where a postmortem diagnosis was reported in the eCRF, the data were medically coded by an independent medical coder who was not involved in patient recruitment, data collection, or analysis. The data collection period continued until 28 March 2024.

Statistical data processing. Baseline patient characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and proportions, while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or as median (interquartile range [IQR]) for non-normally distributed data. Survival analyses were employed to evaluate clinical outcomes. The time to event was defined as the duration from the date of visit 1 to the date of event of interest or the last recorded follow-up date in the eCRF or the date of death for event-free or deceased participants, respectively. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to assess the incidence of all-cause mortality. Additionally, cumulative incidence function estimates accounting for competing risks were analyzed for cardiovascular events or HF-related hospitalizations. Data analysis was conducted for the overall study population and was stratified by LVEF subgroups: HFrEF (LVEF <40%), HFmrEF (LVEF 40-49%), and HFpEF (LVEF ≥50%) [21]. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (version 18.0, Stata Corp LP).

Results

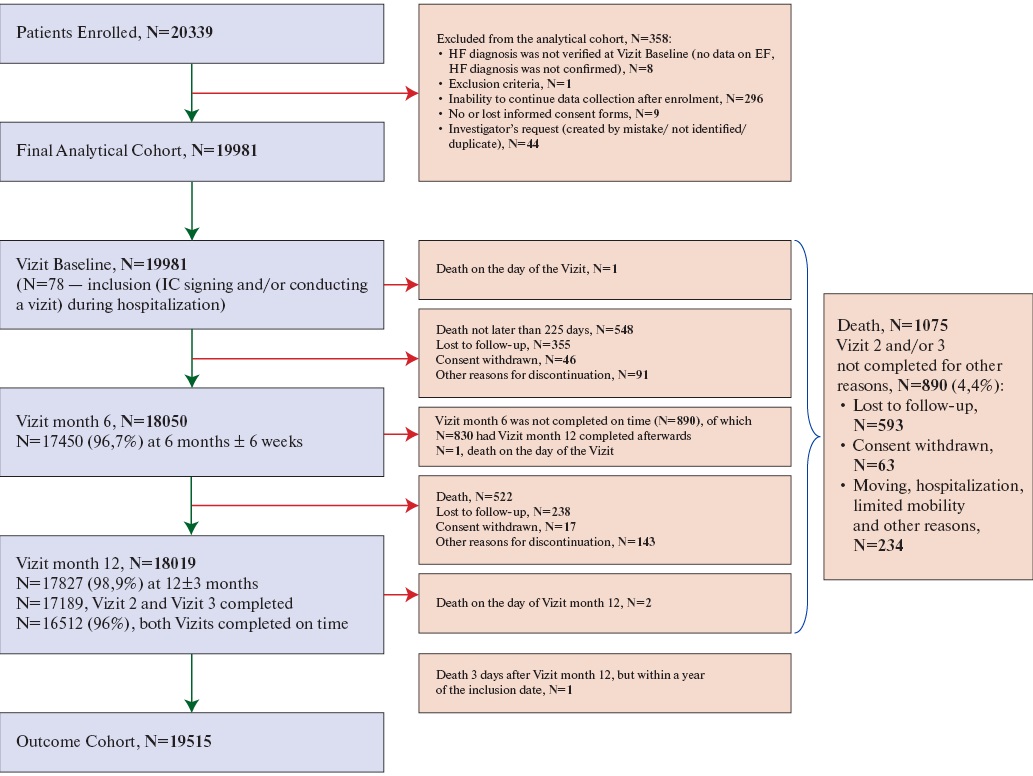

The study involved 199 physicians from 64 locations across the country. Out of 20,339 recruited patients, 19,981 patients met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analytical cohort (Supplemental Figure 1).

Baseline patients’ characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean±SD age of the participants was 64.9±10.9 years (median [IQR]: 66 [ 59-72] years). Males comprised 63.5% of the cohort, and the majority of patients (98.8%) were Caucasian. The median (IQR) duration of HF prior to study inclusion was 24 (3-60) months, and 58 (0.3%) patients underwent heart transplants before enrollment. The mean±SD LVEF was 45.9±12.5%.

Table 1

Baseline patients’ characteristics

|

Parameter |

HFrEF |

HFmrEF |

HFpEF |

Overall |

|

N=6,969 |

N=4,940 |

N=8,072 |

N=19,981 |

|

|

Age, years, mean±SD |

62.1±10.9 |

64.4±10.8 |

67.5±10.4 |

64.9±10.9 |

|

Male, n (%) |

5,432 (77.9) |

3,507 (71.0) |

3,758 (46.6) |

12,697 (63.5) |

|

Race, n (%) |

||||

|

Black/African American |

2 (0.0) |

2 (0.0) |

4 (0.0) |

8 (0.0) |

|

Asian |

109 (1.6) |

68 (1.4) |

46 (0.6) |

223 (1.1) |

|

White |

6,858 (98.4) |

4,870 (98.6) |

8,022 (99.4) |

19,750 (98.8) |

|

Smoking, n (%) |

||||

|

Current smoker |

1,272 (18.3) |

677 (13.7) |

742 (9.2) |

2,691 (13.5) |

|

Former smoker |

1,420 (20.4) |

869 (17.6) |

913 (11.3) |

3,202 (16.0) |

|

Alcohol abuse, n (%) |

||||

|

Current |

62 (0.9) |

39 (0.8) |

37 (0.5) |

138 (0.7) |

|

History of alcohol abuse |

367 (5.3) |

185 (3.7) |

186 (2.3) |

738 (3.7) |

|

BMI, kg/m², n (%) |

N=6,739 |

N=4,792 |

N=7,876 |

N=19,407 |

|

>30 |

2,627 (39.0) |

2,057 (42.9) |

3,771 (47.9) |

8,455 (43.6) |

|

25-30 |

2,529 (37.5) |

1,855 (38.7) |

2,788 (35.4) |

7,172 (37.0) |

|

≤25 |

1,583 (23.5) |

880 (18.4) |

1,317 (16.7) |

3,780 (19.5) |

|

BMI, kg/m², mean±SD |

29.1±5.4 |

29.9±5.6 |

30.5±5.8 |

29.9±5.7 |

|

Blood pressure, mm Hg, mean±SD |

N=6,949 |

N=4,928 |

N=8,061 |

N=19,938 |

|

Systolic blood pressure (SBP), mm Hg |

121.3±18.9 |

126.3±18.1 |

129.8±18.3 |

126.0±18.8 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mm Hg |

75.9±11.2 |

77.7±10.6 |

78.3±10.4 |

77.3±10.8 |

|

Heart Rate, bpm |

N=6,945 |

N=4,926 |

N=8,051 |

N=19,922 |

|

Mean±SD |

77.3±15.3 |

75.0±14.2 |

73.2±12.7 |

75.1±14.1 |

|

ECG heart rhythm, n (%) |

N=6,624 |

N=4,590 |

N=7,558 |

N=18,772 |

|

Sinus rhythm |

4,302 (64.9) |

3,090 (67.3) |

5,454 (72.2) |

12,846 (68.4) |

|

Atrial fibrillation/flutter |

1,888 (28.5) |

1,334 (29.1) |

1,811 (24.0) |

5,033 (26.8) |

|

Pacemaker |

434 (6.6) |

166 (3.6) |

293 (3.9) |

893 (4.8) |

|

Arterial hypertension, n (%) |

5,710 (81.9) |

4,468 (90.4) |

7,605 (94.2) |

17,783 (89.0) |

|

Obesity |

2,828 (40.6) |

2,180 (44.1) |

4,024 (49.9) |

9,032 (45.2) |

|

Dyslipidaemia |

1,747 (25.1) |

1,604 (32.5) |

3,774 (46.8) |

7,125 (35.7) |

|

Type 2 diabetes, n (%) |

1,735 (24.9) |

1,343 (27.2) |

2,394 (29.7) |

5,472 (27.4) |

|

Atrial fibrillation/flutter, n (%) |

2,992 (42.9) |

2,103 (42.6) |

3,406 (42.2) |

8,501 (42.5) |

|

Ischemic heart disease, n (%) |

5,111 (73.3) |

4,023 (81.4) |

5,534 (68.6) |

14,668 (73.4) |

|

History of myocardial infarction, n (%) |

4,099 (58.8) |

3,042 (61.6) |

2,289 (28.4) |

9,430 (47.2) |

|

History of percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) |

2,142 (30.7) |

1,913 (38.7) |

1,807 (22.4) |

5,862 (29.3) |

|

History of coronary artery bypass grafting, n (%) |

797 (11.4) |

751 (15.2) |

740 (9.2) |

2,288 (11.5) |

|

History of heart valve surgery, n (%) |

309 (4.4) |

290 (5.9) |

532 (6.6) |

1,131 (5.7) |

|

Stroke, n (%) |

561 (8.0) |

422 (8.5) |

709 (8.8) |

1,692 (8.5) |

|

Transient ischemic attack, n (%) |

65 (0.9) |

47 (1.0) |

120 (1.5) |

232 (1.2) |

|

Peripheral artery disease, n (%) |

512 (7.3) |

404 (8.2) |

845 (10.5) |

1,761 (8.8) |

|

Chronic Kidney Disease, n (%) |

2,766 (39.7) |

2,149 (43.5) |

4,009 (49.7) |

8,924 (44.7) |

|

Serum creatinine, µmol/L |

N=5,635 |

N=4,080 |

N=6,883 |

N=16,598 |

|

Median (IQR) |

98.0 (84.8-114.6) |

95.0 (82.0-111.0) |

90.0 (77.0-105.3) |

94.0 (80.0-110.0) |

|

eGFR CKD-EPI 2021, mL/min/1.73 m² |

N=5,635 |

N=4,080 |

N=6,883 |

N=16,598 |

|

Median (IQR) |

71.0 (57.0-86.5) |

70.9 (57.4-86.8) |

69.4 (55.9-84.5) |

70.3 (56.7-85.7) |

|

Hemoglobin, g/L |

N=5,378 |

N=3,881 |

N=6,575 |

N=15,834 |

|

Mean±SD |

139.7±18.9 |

138.1±18.3 |

134.5±17.9 |

137.1±18.5 |

|

Asthma, n (%) |

114 (1.6) |

121 (2.4) |

334 (4.1) |

569 (2.8) |

|

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, n (%) |

525 (7.5) |

282 (5.7) |

434 (5.4) |

1,241 (6.2) |

|

Duration of HF, months, median (IQR) |

17 (3.0-56.9) |

20 (3.1-60.0) |

24 (3.3-60.0) |

24 (3.0-60.0) |

|

History of admission with HF, n (%) |

2,939 (42.2) |

1,541 (31.2) |

1,926 (23.9) |

6,406 (32.1) |

|

LVEF, %, (Mean±SD) |

32.3±5.8 |

44.6±2.9 |

58.4±5.7 |

45.9±12.5 |

|

NYHA, n (%) |

||||

|

I |

419 (6.0) |

472 (9.6) |

1,141 (14.1) |

2,032 (10.2) |

|

II |

3,097 (44.4) |

2,760 (55.9) |

4,892 (60.6) |

10,749 (53.8) |

|

III |

3,252 (46.7) |

1,626 (32.9) |

1,956 (24.2) |

6,834 (34.2) |

|

IV |

201 (2.9) |

82 (1.7) |

83 (1.0) |

366 (1.8) |

|

NT-proBNP, pg/mL |

N=1,409 |

N=1,412 |

N=2,971 |

N=5,792 |

|

Median (IQR) |

1,265 (620.7; 2554.0) |

784.5 (392.9; 1797.5) |

504 (274.0; 1036.0) |

698 (340.0; 1543.5) |

|

BNP, pg/mL |

N=183 |

N=138 |

N=249 |

N=570 |

|

Median (IQR) |

443 (198.6; 1178.0) |

474 (233.0; 1230.0) |

408 (204.0; 956.0) |

432.5 (212.1; 1111.0) |

|

History of heart transplant, n (%) |

1 (0.0%) |

2 (0.0%) |

55 (0.7%) |

58 (0.3%) |

Note: N for variables indicates number of non-missing values. The data exclude 23 patients with uncertain PCI surgery timing, 4 with uncertain CABG surgery timing, and 4 with uncertain heart valve surgery timing; for HF hospitalization history, any past episode was considered.

Abbreviations: SD — standard deviation, n — number (or count), BMI — body mass index, bpm — beats per minute, ECG — electrocardiogram, HF — heart failure, LVEF — left ventricular ejection fraction, NYHA — New York Heart Association, NT-proBNP — NT-terminal pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide, BNP — brain natriuretic peptide, IQR — interquartile range, eGFR — Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, CKD-EPI-Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration, HFrEF — HF with reduced ejection fraction, HFmrEF — HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction, HFpEF — HF with preserved ejection fraction, CKD — chronic kidney disease.

The HFrEF was reported in 6,969 (34.9%) patients, HFmrEF in 4,940 (24.7%) patients, and HFpEF in 8,072 (40.4%) patients. The majority of the patients (53.8%) were classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) II functional class. The BNP and/or NT-proBNP levels were available in a total of 6,297 (31.5%) patients: in 1,559 (22.4%) of HFrEF, 1,535 (31.1%) of HFmrEF, and 3,203 (39.7%) of HFpEF patients. The most prevalent comorbidities included arterial hypertension (AH), ischemic heart disease (IHD), obesity, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and atrial fibrillation or flutter (AF) (Table 1).

Heart failure medical and device therapy

At baseline, GDMT was prescribed as follows: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi; angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNi)) in 80.9%, beta-blockers (BB) in 78.8%, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) in 59.3%, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) in 18.4% of patients. For all GDMT classes, an increased frequency of prescription was noted after visit 1 (Table 2).

Table 2

Baseline and post enrollment (visit 1) medications

|

Drug class |

HFrEF, N=6,969 |

HFmrEF, N=4,940 |

HFpEF, N=8,072 |

Total, N=19,981 |

||||

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|||||

|

Before |

After |

Before |

After |

Before |

After |

Before |

After |

|

|

ACEi |

2,367 (34.0) |

2,278 (32.7) |

2,196 (44.5) |

2,299 (46.5) |

3,369 (41.7) |

3,669 (45.5) |

7,932 (39.7) |

8,246 (41.3) |

|

ARB |

849 (12.2) |

846 (12.1) |

1,013 (20.5) |

1,069 (21.6) |

2,964 (36.7) |

3,215 (39.8) |

4,826 (24.2) |

5,130 (25.7) |

|

ARNi |

2,301 (33.0) |

3,190 (45.8) |

839 (17.0) |

1,181 (23.9) |

348 (4.3) |

502 (6.2) |

3,488 (17.5) |

4,873 (24.4) |

|

RAASia |

5,484 (78.7) |

6,262 (89.9) |

4,032 (81.6) |

4,521 (91.5) |

6,652 (82.4) |

7,347 (91.0) |

16,168 (80.9) |

18,130 (90.7) |

|

BBb |

5,748 (82.5) |

6,272 (90.0) |

4,001 (81.0) |

4,374 (88.5) |

6,004 (74.4) |

6,543 (81.1) |

15,753 (78.8) |

17,189 (86.0) |

|

MRA |

5,230 (75.0) |

6,071 (87.1) |

3,089 (62.5) |

3,718 (75.3) |

3,533 (43.8) |

4,486 (55.6) |

11,852 (59.3) |

14,275 (71.4) |

|

SGLT2ic |

1,996 (28.6) |

3,380 (48.5) |

873 (17.7) |

1,441 (29.2) |

808 (10.0) |

1,316 (16.3) |

3,677 (18.4) |

6,137 (30.7) |

|

Ivabradin |

304 (4.4) |

387 (5.6) |

175 (3.5) |

212 (4.3) |

209 (2.6) |

271 (3.4) |

688 (3.4) |

870 (4.4) |

|

Digoxin |

788 (11.3) |

873 (12.5) |

449 (9.1) |

489 (9.9) |

525 (6.5) |

565 (7.0) |

1,762 (8.8) |

1,927 (9.6) |

|

Loop diuretics |

3,418 (49.0) |

4,002 (57.4) |

1,802 (36.5) |

2,181 (44.1) |

2,319 (28.7) |

2,943 (36.5) |

7,539 (37.7) |

9,126 (45.7) |

|

Thiazide/thiazide-like diuretics |

207 (3.0) |

209 (3.0) |

321 (6.5) |

342 (6.9) |

1,544 (19.1) |

1,588 (19.7) |

2,072 (10.4) |

2,139 (10.7) |

|

Acetazolamide |

60 (0.9) |

77 (1.1) |

21 (0.4) |

23 (0.5) |

39 (0.5) |

45 (0.6) |

120 (0.6) |

145 (0.7) |

|

Oral anticoagulants |

2,879 (41.3) |

3,211 (46.1) |

1,976 (40.0) |

2,170 (43.9) |

3,160 (39.1) |

3,443 (42.7) |

8,015 (40.1) |

8,824 (44.2) |

|

Antiarrhythmicsd |

1,058 (15.2) |

1,173 (16.8) |

552 (11.2) |

617 (12.5) |

884 (11.0) |

960 (11.9) |

2,494 (12.5) |

2,750 (13.8) |

|

Omega-3-PUFAs |

63 (0.9) |

95 (1.4) |

36 (0.7) |

61 (1.2) |

41 (0.5) |

76 (0.9) |

140 (0.7) |

232 (1.2) |

|

DHP CCBs |

525 (7.5) |

549 (7.9) |

846 (17.1) |

939 (19.0) |

2,438 (30.2) |

2,785 (34.5) |

3,809 (19.1) |

4,273 (21.4) |

|

non-DHP CCBs |

24 (0.3) |

28 (0.4) |

31 (0.6) |

32 (0.6) |

71 (0.9) |

85 (1.1) |

126 (0.6) |

145 (0.7) |

|

Statins |

4,646 (66.7) |

5,010 (71.9) |

3,778 (76.5) |

4,031 (81.6) |

5,861 (72.6) |

6,562 (81.3) |

14,285 (71.5) |

15,603 (78.1) |

|

Nitrates |

154 (2.2) |

164 (2.4) |

133 (2.7) |

141 (2.9) |

171 (2.1) |

196 (2.4) |

458 (2.3) |

501 (2.5) |

|

Other antianginals (ranolazine, trimetazidine, nicorandil) |

314 (4.5) |

456 (6.5) |

257 (5.2) |

362 (7.3) |

658 (8.2) |

927 (11.5) |

1,229 (6.2) |

1,745 (8.7) |

Note: a — the sum of ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and ARNIs does not equal the total for RAAS inhibitors because the design of the eCRF, which required only the start and end dates of therapy, unables the identification of the exact sequence of medication use for some patients; b — any class member except sotalol and intraocular agents was considered; c — any class member was considered; d — amiodarone, sotalol, etacizine, flecainide, propafenone, and lappaconitine hydrobromide were included, while digoxin and non-DHP CCBs were excluded.

Abbreviations: ACEi — angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARBs — angiotensin receptor blockers, ARNi — angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors, RAASi — renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, BB — beta-blockers, MRAs — mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, SGLT2i — sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, Omega-3 PUFAs — omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, DHP CCBs — dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, non-DHP CCBs — non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, HFrEF — heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HFpEF — heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFmrEF — heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction.

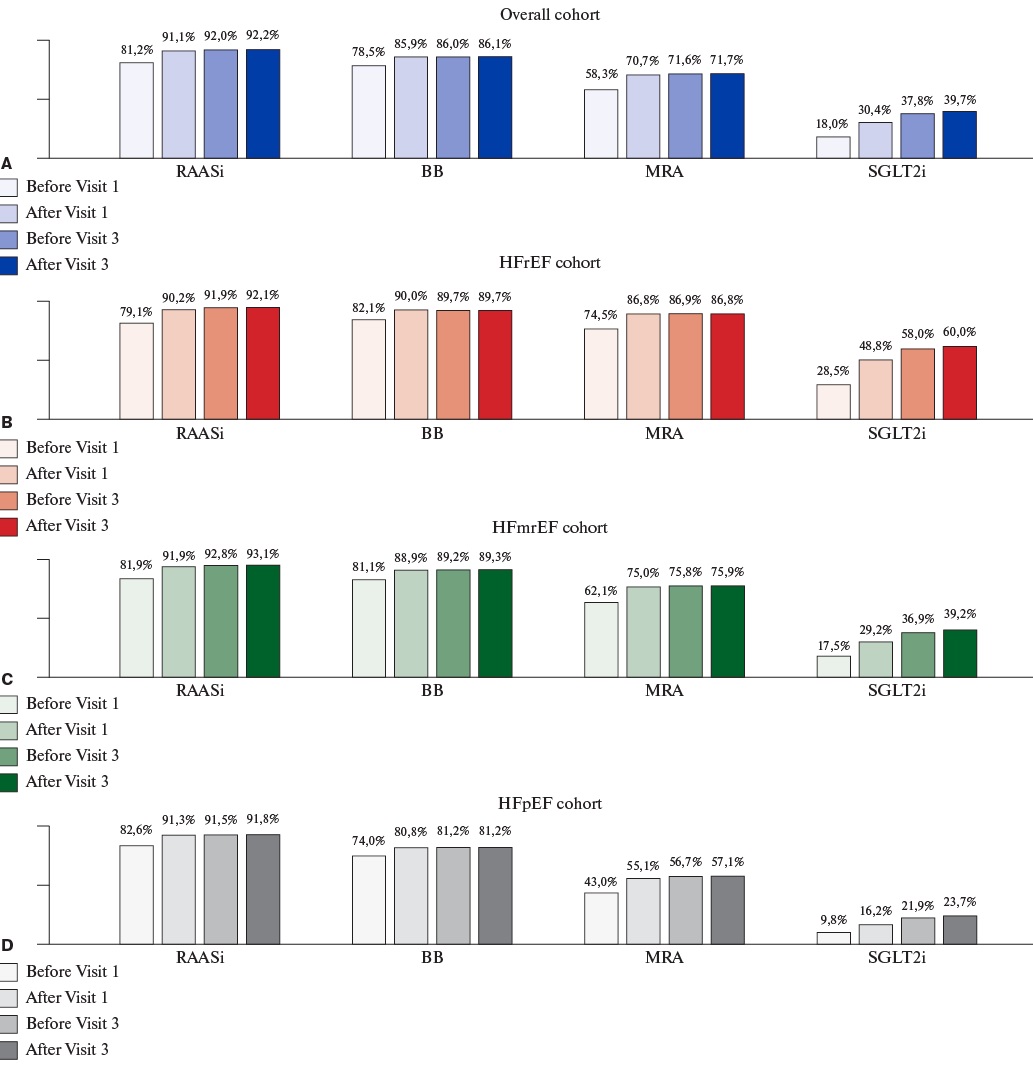

Analysis of the frequency of GDMT class prescription over the study period in 18,019 patients who completed visit 3 of the study, demonstrated a two-fold increase for SGLT2i (baseline: 18.0%; after visit 3: 39.7%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Guideline-directed medical therapy prescription over the study period for overall cohort and HF phenotypes (N=18,019, patients who completed visit 3 of the study).

Abbreviations: BB — beta-blockers, HFrEF — heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HFmrEF — heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction, HFpEF — heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, LVEF — left ventricular ejection fraction, MRAs — mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, RAASi — renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, SGLT2i — sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors.

Among 6,047 patients with HFrEF who completed visit 3, all four classes of GDMT were prescribed to 1,281 (21.2%) patients before visit 1; 2,226 (36.8%) patients after visit 1; 2,724 (45.0%) patients before visit 3; and 2,819 (46.6%) patients at the end of their participation in the study.

At baseline, among patients in the HFrEF cohort, 488 (7.0%) patients had an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), 51 (0.7%) patients had a CRT device, 154 (2.2%) patients had a cardiac resynchronization therapy with a defibrillator (CRT-D), and 5 (0.1%) patients had a mechanical circulatory support device. At the end of the study, an ICD, CRT, CRT-D, and mechanical circulatory support device were additionally implanted in 134 (1.9%), 25 (0.4%), 63 (0.9%), and 7 (0.1%) patients with HFrEF.

Vaccinations

At baseline and during the follow-up period, 6,177 (30.9%) patients had a history of any vaccination (influenza, pneumococcal infection or COVID-19), of whom the majority (5,368 patients, 86.9%) received only COVID-19 vaccination. A total of 730 (3.7%) and 131 (0.7%) patients were vaccinated against influenza and pneumococcal infection, respectively.

Mortality and heart failure hospitalizations

Mortality and HF hospitalization outcome data were available for 19,515 patients (Table 3). Over a median (IQR) follow-up of 376 (366-399) days, 1,075 (5.5%) patients died, including one patient who died on the day of visit 1. A total of 25 (0.1%) patients underwent heart transplantation, and 5,000 (25.6%) were readmitted. Cardiovascular causes accounted for 68.1% of deaths (732/1,075). 22.4% (1,620) of the total 7,218 hospitalizations were due to HF.

Table 3

Outcomes in the overall and HF phenotypes

|

Parameter |

HFrEF |

HFmrEF |

HFpEF |

Overall |

|

Patients with known outcomes after visit 1, n (%) |

6,776 (34.7) |

4,828 (24.7) |

7,911 (40.5) |

19,515 (100.0) |

|

Follow-up duration, median (IQR) |

375 (366-397) |

375 (366-396) |

378 (367-402) |

376 (366-399) |

|

Outcomes over the entire follow-up period, n (%) |

||||

|

Deceased patients |

582 (8.6) |

235 (4.9) |

258 (3.3) |

1,075 (5.5) |

|

Causes of death |

||||

|

— Non-cardiovascular, % of all cases |

117 (20.1) |

66 (28.1) |

74 (28.7) |

257 (23.9) |

|

— Cardiovascular, % of all cases |

412 (70.8) |

155 (66.0) |

165 (64.0) |

732 (68.1) |

|

— Unknown, % of all cases |

53 (9.1) |

14 (6.0) |

19 (7.4) |

86 (8.0) |

|

Patients hospitalized for any cause |

2,005 (29.6) |

1,247 (25.8) |

1,748 (22.1) |

5,000 (25.6) |

|

Patients hospitalized for cardiovascular events |

1,415 (20.9) |

854 (17.7) |

983 (12.4) |

3,252 (16.7) |

|

Patients hospitalized for HF |

737 (10.9) |

311 (6.4) |

239 (3.0) |

1,287 (6.6) |

|

Total number of hospitalizations |

3,007 |

1,753 |

2,458 |

7,218 |

|

Hospitalisation for HF, % of all cases |

951 (31.6) |

369 (21.0) |

300 (12.2) |

1,620 (22.4) |

|

Hospitalisation for cardiovascular causes, % of all cases |

1,909 (63.5) |

1,095 (62.5) |

1,247 (36.1) |

4,251 (58.9) |

|

12-months Kaplan-Meier estimates |

||||

|

All-cause mortality, % |

8.1 (7.5-8.8) |

4.6 (4.1-5.3) |

3.1 (2.8-3.5) |

5.2 (4.9-5.6) |

|

All-cause mortality, per 100 PY |

8.5 (7.8-9.2) |

4.8 (4.2-5.4) |

3.2 (2.8-3.6) |

5.4 (5.1-5.7) |

|

Cardiovascular death, % |

5.8 (5.3-6.4) |

3.1 (2.7-3.7) |

2.0 (1.8-2.4) |

3.6 (3.4-3.9) |

|

Cardiovascular death, per 100 PY |

6.0 (5.4-6.6) |

3.2 (2.7-3.7) |

2.1 (1.8-2.4) |

3.7 (3.4-4.0) |

|

All-cause hospitalization, % |

29.1 (28.0-30.2) |

25.1 (23.9-26.4) |

21.3 (20.4-22.2) |

24.9 (24.3-25.6) |

|

All-cause hospitalization, per 100 PY |

35.5 (34.0-37.2) |

29.3 (27.7-31.1) |

24.2 (23.0-25.4) |

29.2 (28.4-30.1) |

|

Cardiovascular hospitalization, % |

21.5 (20.5-22.5) |

18.0 (16.9-19.2) |

12.6 (11.9-13.4) |

17.0 (16.5-17.6) |

|

Cardiovascular hospitalization, per 100 PY |

24.7 (23.4-26.0) |

19.9 (18.6-21.4) |

13.6 (12.7-14.5) |

18.8 (18.2-19.5) |

|

HF hospitalization, % |

11.9 (11.1-12.8) |

7.0 (6.3-7.9) |

3.3 (2.9-3.7) |

7.2 (6.8-7.6) |

|

HF hospitalization, per 100 PY |

12.9 (12.0-13.9) |

7.3 (6.5-8.1) |

3.3 (2.9-3.8) |

7.5 (7.1-7.9) |

|

12-months cumulative incidence failure estimates accounting for competing risks |

||||

|

Cardiovascular death, % |

5.7 (5.2-6.3) |

3.1 (2.6-3.6) |

2.0 (1.7-2.4) |

3.6 (3.3-3.8) |

|

All-cause hospitalization, % |

28.4 (27.4-29.5) |

24.8 (23.6-26.0) |

21.1 (20.2-22.0) |

24.5 (23.9-25.2) |

|

Cardiovascular hospitalization, % |

19.9 (18.9-20.8) |

16.9 (15.9-18.0) |

11.9 (11.2-12.6) |

15.9 (15.4-16.4) |

|

HF hospitalization, % |

10.4 (9.7-11.1) |

6.2 (5.5-6.9) |

2.9 (2.5-3.3) |

6.3 (6.0-6.7) |

Note: cumulative incidences by Kaplan-Meier and by failure estimates, are presented as the 95% confidence interval in brackets; for cardiovascular death, the risk of death due to other causes was considered; for all-cause hospitalization, the competing risk of all-cause death was considered; for HF hospitalization, the competing risk of all-cause death or hospitalization due to other causes was considered.

Abbreviations: HF — heart failure, HFrEF — heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HFpEF — heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFmrEF — heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction, PY — patient-years.

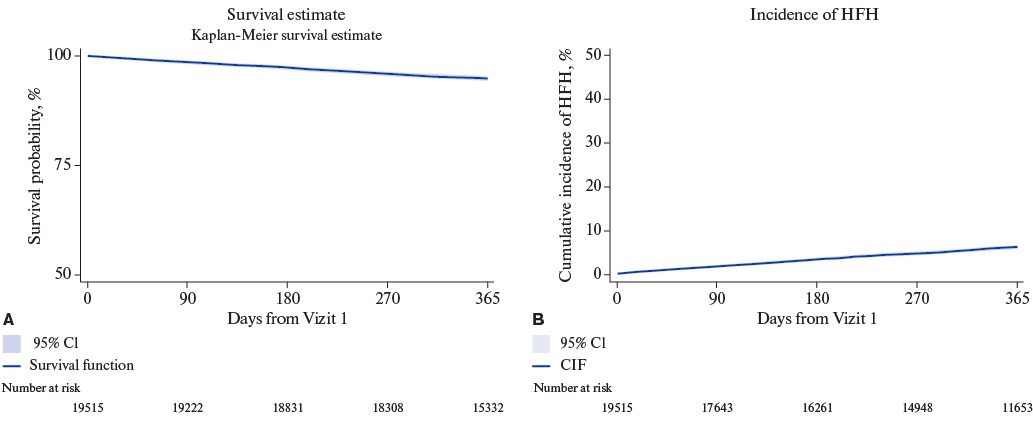

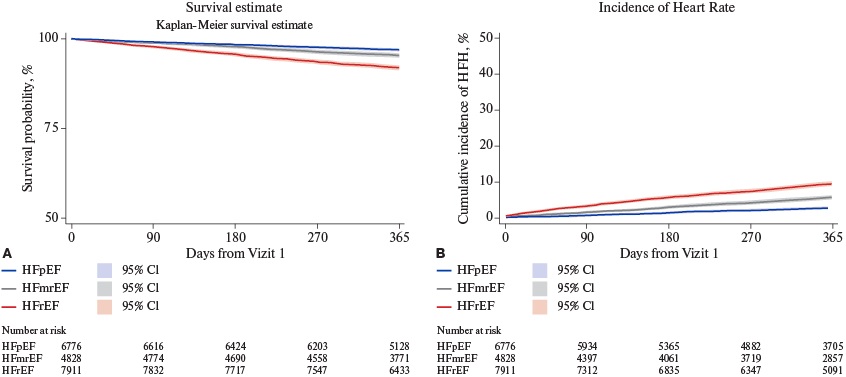

The overall mortality rate (95% CI) at 12 months was 5.2% (4.9-5.6%). The cumulative incidence (95% CI) of HF hospitalization, accounting for competing risk of all-cause death, was 6.3% (6.5-6.7%) (Figure 2). Patients with HFrEF had the highest 12-month mortality (8.1%, 95% CI 7.5-8.8%) and HF hospitalization (10.4%, 95% CI 9.7-11.1%) rates, while the lowest rates were observed in the HFpEF subgroup with 12-month mortality of 3.1% (95% CI 2.8-3.5%) and HF hospitalization of 2.9% (95% CI 2.5-3.3%) (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Figure 2. Cumulative Survival and Incidence of HFH in the Overall Cohort.

Abbreviations: CIF — cumulative incidence function, CI — confidence interval, HFH — heart failure hospitalization.

Figure 3. Cumulative Survival and Incidence of HFH in the cohorts stratified per LVEF.

Abbreviations: HFrEF — heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HFmrEF — heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction, HFpEF — heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFH — heart failure hospitalization, CI — confidence interval.

Discussion

The PRIORITY-HF represents the first large-scale prospective study of HF outpatients in the Russian Federation. The pragmatic design of the study enabled a comprehensive characterization of HF outpatients and their routine treatment patterns. We found that HF outpatients in the Russian Federation (i) are relatively young, predominantly male and exhibit a high burden of comorbidities; (ii) experience a relatively low incidence of adverse outcomes over a 1-year follow-up period; (iii) were frequently prescribed individual classes of GDMT across the entire spectrum of LVEF values though paralleled with (iv) sub-optimal use of quadruple therapy and device therapies among patients with HFrEF. These findings provide a foundation for the development of national targeted programs aimed at improving HF quality of care, educational programs for primary care physicians, and further expansion of reimbursement for HF medications.

HF has been traditionally viewed as a disease of predominantly older persons. In our study, the average age of HF outpatients across all LVEF phenotypes was notably lower than that reported in contemporary large-scale randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and cohort studies from high-income countries [22][23]. Our study also revealed a higher prevalence of comorbidities, including AH (89.0%), IHD (73.4%), obesity (45.2%), CKD (44.7%), and AF (42.5%). In comparison, multicentre HF registries across Europe, the USA, and Asia report the proportion of patients with AH ranging from 38% to 85%, IHD from 19.0% to 59.0%, AF from 4.0% to 38.0%, and CKD from 8.0% to 53.0% [12][15][24]. The relatively young age and high comorbidity burden among HF outpatients in the Russian Federation might reflect the evolving cardiorenometabolic disorders within the general population and signal a potentially growing burden on the healthcare system. Indeed, recent trends indicate an increasing prevalence of HF in younger individuals [25][26]. As such, early identification and management of the risk factors, even at the preclinical stage of HF, are of utmost importance [27][28].

The observed differences in HF phenotypes based on EF align with the previous findings [22]. Patients with HFpEF were older and exhibited a higher frequency of non-cardiac comorbidities compared to those with HFrEF and HFmrEF. Also consistent with data from other studies, patients with HFrEF were younger and predominantly male but more likely to have a history of smoking, alcohol abuse, IHD, and prior myocardial infarction. Despite a shorter duration of HF, patients with HFrEF experienced a more severe disease state, as evidenced by a higher proportion of patients in NYHA class III-IV and elevated NP levels. HFmrEF patients occupied an intermediate position, sharing greater similarities with HFrEF and, in some cases, even exceeding it in terms of frequency of IHD and revascularization procedures.

In recent years, the relative prevalence of HFpEF among HF phenotypes has been approximated at around 50% [29]. The proportion of patients with HFpEF in the studied cohort was 40.4%; of 59.6% patients, 34.9% and 24.7% had HFrEF and HFmrEF, respectively. The distribution of HF phenotypes across LVEF subgroups may be attributed to the younger age of patients, male predominance, and higher prevalence of IHD among the various HF risk factors. Indeed, in HF cohorts with a higher proportion of elderly patients, a greater proportion of women and a higher prevalence of HFpEF have been reported, with latter reaching up to 69% in Japan [30]. Another factor that might have an impact on the distribution of HF phenotypes is the limited availability of NP testing in routine clinical practice, potentially leading to difficulties in the diagnosis of HFpEF. This limitation could have resulted in the exclusion of some eligible HFpEF patients from the study. Unlike the high-income countries, where NP testing is widely integrated into the diagnostic work-up for HF, it remains underutilized in the Russian Federation, with echocardiography usually being used as the first diagnostic step for HF. A prior study of outpatient practices in seven regions of the Russian Federation found that NP testing in HF outpatients was performed in less than 1% of cases [31]. In the present study, NP values were available for around one-third of HF patients (31.5%), with a slightly higher rate in HFpEF patients (39.7%). The underutilization of NP testing is a widely recognized global issue in both in-patient and primary care settings despite strong recommendations from professional societies [32]. For example, in the United Kingdom, although the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends NP testing for suspected HF to facilitate timely echocardiography and a specialist consultation within two weeks, it is not performed in at least 60% of the cases [33]. In addition to the use for HF diagnosis and risk stratification, NP testing is also recognized in official documents of the Ministry of Health of Russia as (1) a metric of quality of care according to clinical guidelines for HF, (2) a laboratory test in the standard of medical care for HF diagnosis, and (3) a key monitored parameter in primary care follow-up of HF patients. Nevertheless, the data obtained in the present study reflects limited use of NP testing and emphasizes the need for additional organizational steps for wider implementation of this diagnostic and prognostic marker in real-world clinical practice.

This study demonstrated a high frequency of baseline GDMT prescription in patients across all HF phenotypes. The proportions of HFrEF patients prescribed RAASi, BB, and MRAs following enrollment in this study (90%, 90%, and 87.1%, respectively) for each or at least one class were notably higher than in previously published population studies from Denmark (76.5%, 80.8%, and 30.1%) [34] and Sweden (92%, 91.2%, and 40.8%) [35]. The US CHAMP-HF registry (73.4%, 67.0%, and 33.4% among eligible patients) [24], ASIAN-HF registry (77%, 79%, and 58%) [36], and the global G-CHF registry (80.1%, 84.5%, and 65.2%) [23] reported slightly lower prescription rates compared to our study. Moreover, throughout the study, the use of SGLT2i increased steadily across all LVEF subgroups, reaching 39.7% by the end of the study. In a multinational EVOLUTION-HF study with a recruitment period comparable to that of the present study, the highest uptake of SGLT2i following first HF admission was 35% [37].

Our study showed an improvement in GDMT use from baseline to visit 3, highlighting the value of disease registries as crucial tools for improving both the quality of care and outcomes in HF patients. However, during follow-up, the frequency of GDMT classes use (except for SGLT2i) changed insignificantly. Notably, only 46.6% of HFrEF patients received quadruple therapy by the end of the study, reflecting clinical inertia and underscoring the need for overcoming physician-related (mainly perceived) barriers, regular assessment of quality of care, and patient engagement in the HF management process [38]. Expanding the use of device-based therapies in HFrEF patients and implementing regular vaccination programs represent additional opportunities for improving HF outcomes [39].

In general, HF outcomes are influenced by factors such as patients’ demographic factors, comorbidities, accessibility, and quality of medical care. Global meta-analysis of HF patients with a history of hospitalization report one-year mortality rates ranging from 8% to 37% and HF readmission rates from 12% to 63% [10]. In another meta-analysis of 60 studies involving approximately 1.5 million patients with HF, the average 1-year mortality rate was 13.5%, with a range of 1.6% to 33.3% [13]. In this study, the all-cause mortality rate (5.2% in the total cohort) was lower than in most international registries and RCTs, aligning closely with data from the ASIAN-HF registry (6.8% in the entire cohort, 7.6% in HFrEF and 3.7% in HFpEF) [40]. Notably, the overall mortality rate in patients with HFpEF was 2.6 times lower than those with HFrEF, contrasting with the studies suggesting similar survival rates across all LVEF phenotypes [35]. The RCTs involving HFpEF patients report 1-year mortality rates ranging from 4.6% to 7.6% [41-43]. Still, a similarly low HFpEF mortality (3.2 per 100 patient-years) was observed in the sub-analysis of the CHARM-Preserved for Eastern European countries [44]. For comparison, all-cause mortality ranged from 2.1 to 2.6 per 100 patient-years in the Russian Federation/Georgia subgroup of the TOPCAT trial [45], and it varied from 1.1% to 5.0% in RCTs involving high-risk patients with AH, diabetes, AF, or IHD [46]. The explanation of our findings on relatively better survival in overall HF outpatients and particularly in HFpEF necessitates consideration of several factors. First, most RCTs employ risk enrichment inclusion criteria to ensure an adequate number of primary endpoint events. Recent RCTs have also extended eligibility criteria on patients stabilised after admission for worsening HF, thereby substantially increasing the likelihood of adverse outcomes. Secondly, the patient cohort in this study was relatively young for those with HFpEF. Notably, the mortality rate in HFpEF patients under 65 years of age is considerably lower (1.9 to 3.2 deaths per 100 patient-years) compared to that observed in HFpEF patients aged 85 years or older (16.7 deaths per 100 patient-years) [47]. Finally, our study highlighted a high uptake of SGLT2i and other recommended drugs for HFpEF. Specifically, baseline prescription rates in this study for SGLT2i, MRAs, and ARNi in HFpEF patients were 16.3%, 55.6%, and 6.2%, respectively, compared to 39% for MRAs and 4% for ARNi in the DELIVER trial [41], and 14% for SGLT2i and 8.5% for ARNi in the FINEARTS trial [47]. Given the challenges in diagnosing HFpEF, further clinical studies are necessary to understand whether the younger age, lower NP levels, reduced diuretic use, and relatively favourable prognosis reflect a positive trend in the Russian Federation towards timely HFpEF diagnosis at early stages of the disease or, conversely, indicate a problem of HF overdiagnosis.

Study limitations. The study has a few limitations. First, enrollment of only those outpatients who agreed to participate in the study carries a systematic risk of recruiting patients with less severe HF. However, this study is the largest current sample of outpatients with HF in the Russian Federation. The prospective multicentre design and the lack of strict inclusion criteria, as well as centralized data collection and analysis, enhance the generalisability of the results. Moreover, lower mortality rates in Eastern Europe, including the Russian Federation, have also been documented in other studies [11], potentially linked with higher GDMT prescription rates. Second, collecting data only on LVEF limited the ability to verify compliance with HFpEF diagnostic criteria recommended by current HF guidelines. The exclusion of NP measurement requirements for patient enrolment aimed to reflect real-world practices in diagnosing HF and to minimize the possibility of including patients predominantly with HFrEF. However, HF diagnosis by the opinion of physician aligns with methods used for patient recruitment in other registries such as the Swedish HF registry [35]. Third, reliance on the clinician-reported clinical data could introduce bias or gaps in data capture. For example, the frequency of alcohol abuse across all LVEF subgroups was reported relatively lower (4.4% in the total cohort) compared to global estimates of 22.5% to 30% [12-23], potentially due to underreporting or differences in the study criteria used (in this study, alcohol abuse was defined as consumption exceeding 10 units per week). Also, events of interest, such as deaths and hospitalizations in this study were documented through direct communication with the patient or relatives or via electronic medical record assessment. Still, given the absence of a comprehensive federal medical information system across all regions and the lack of official, standalone HF-related statistical data in the Russian Federation, this approach represented the most feasible method for assessing HF prognosis in such a large-scale real-world study.

Conclusion

HF outpatients in Russia are relatively young patients with a high burden of comorbidities. The prescription rates for individual GDMT classes were high, however, the uptake of quadruple therapy remained suboptimal in patients with HFrEF. Annual mortality and HF hospitalization rates were relatively low but varied across EF phenotypes with numerically higher rates in patients with HFrEF. Further implementation studies for tailored healthcare strategies in Russia are needed to improve HF quality of care and patients’ outcomes.

Acknowledgments. The authors are grateful to all heads of health facilities for their assistance in organizing and conducting the study, as well as the patients who participated in the study.

Relationships and Activities. The study conduction and analysis were supported by AstraZeneca.

Appendix

The study investigators’ names and the affiliations

|

List of Investigators |

Affiliations |

|

Kozhevnikova M. V., Zheleznykh E. A., Slepova O. A., Andreev D. A. (Professor), Suchkova S. A. |

I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, University Clinical Hospital No. 1, Moscow, Russia |

|

Kuzmin A.I. |

Central Clinical Hospital "RZhD-Medicine", Moscow, Russia |

|

Ageev F. T. (Professor), Polyanskaya T. A., Zhigunova L. V., Guchaev R. V., Dergousov P. V. |

E.I. Chazov National Medical Research Center of Cardiology, Moscow, Russia |

|

Sarycheva A. A., Davitashvili S. A. |

Clinical Hospital No. 1 of the Presidential Executive Office of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia |

|

Popovskaya Yu. V., Dombrovskaya E. A. |

Voronezh regional clinical hospital No. 1, Voronezh, Russia |

|

Antonova A. A. |

Lipetsk Regional Clinical Hospital, Lipetsk, Russia |

|

Moskalyuk M. I. |

LLC "Management Company "MEDASIST", Kursk, Russia |

|

Tkhorikova V. N. |

LLC "Promedica", Belgorod, Russia |

|

Sotnikova T. A. |

LLC "Firm "Medical Diagnostic Technologies", Stary Oskol, Russia |

|

Kotlyarova M. V. |

LLC "Clinic of Medical Expertise", Vladimir, Russia |

|

Fedotov S. Yu. |

E.I. Korolev Kostroma Regional Clinical Hospital, Kostroma, Russia |

|

Filippov E. V. (Professor), Moseychuk K. A. |

I.P. Pavlov Ryazan State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Ryazan Region OKKD, Ryazan, Russia |

|

Kulibaba E. V., Timofeeva E. S., Parfenova N. D., Saverova Yu. S. |

City Hospital No. 4 of Vladimir, Vladimir, Russia |

|

Borodkin A. V. |

Tambov Central District Hospital, Tambov, Russia |

|

Zhukov N. I., Bukanova T. Yu., Timofeeva E. V. |

Regional clinical cardiology dispensary, Tver, Russia |

|

Zolotareva E. A., Kruglova I. V., Lazurina I. E. |

Regional Clinical Hospital, Yaroslavl, Russia |

|

Aramyan I. G. |

City Polyclinic No. 2 of the Moscow City Healthcare Department, Moscow, Russia |

|

Klimenko A. S. |

Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia |

|

Suslikov A.V., Zherebker E. M. |

Hospital of the Pushchino Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushchino, Russia |

|

Dovgolis S.A. |

LLC "Family Polyclinic No. 4", Korolev, Russia |

|

Andreenkova Yu. S. |

Polyclinic No. 7, Smolensk, Russia |

|

Lopata N. S. |

N.I. Pirogov National Medical and Surgical Center of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Consultative and Diagnostic Center "Arbatsky", Moscow, Russia |

|

Kondrashina S. A., Konchits М. А. |

Bryansk Regional Cardiology Dispensary, Bryansk, Russia |

|

Grushetskaya I. S., Mosarygina А. I. |

Regional clinical cardiology dispensary, Ryazan, Russia |

|

Timofeeva I. V. |

City Polyclinic No. 1, Vladimir, Russia |

|

Kozmina M. E. |

LLC "Standard-MVS", Voronech, Russia |

|

Dyukova I. A., Mitroshina T. N. |

LLC "Mediscan", Orel, Russia |

|

Tsareva V. M. |

Polyclinic No. 6, Smolensk, Russia |

|

Goryacheva A. A. |

LLC "Treatment and Diagnostic Clinic CardioVita", Smolensk, Russia |

|

Barabanova T. Yu., Prikhodko T. N. |

Tula City Hospital No. 13, Tula, Russia |

|

Dabizha V. G. |

Tula Regional Clinical Hospital, Tula, Russia |

|

Khokhlov R. A. |

Voronezh Regional Clinical Consultative and Diagnostic Center, Voronezh, Russia |

|

Shilova A. S., Shchekochikhin D. Yu. |

N.I. Pirogov City Clinical Hospital No. 1 of the Moscow City Healthcare Department, Moscow, Russia |

|

Tkacheva O. N. (Professor), Alimova Е. R., Zakiev V. D. |

N.I. Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Russian Gerontological Scientific and Clinical Center, Moscow, Russia |

|

Gromov I.V., Gavrilin A. A. |

LLC "Clinic of High-Tech Medicine-YUG", Lyubertsy, Russia |

|

Doronina V. S. |

Consultative and Diagnostic Polyclinic No. 1 of Primorsky District, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Zherlitsina E. A., Plotnikova N. E. |

City Consultative and Diagnostic Center No. 1, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Maslov S. V., Borisova V. V. |

Medical center "Twenty-first century", Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Pavlova O. B. |

Joint Stock Company "CardioClinic", Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Melekhova E. Yu., Potapenko A. V. |

City Polyclinic No. 109, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Sitnikova M. Yu. (Professor), Lyasnikova E. A., Fedorova D. N. |

V.A. Almazov National Medical Research Centre of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Zhuk V. S., Zelyanina E. L. |

LLC "Research and Treatment Center "Deoma", Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Shumilova N. V. |

Central Polyclinic, N. A. Semashko SMCC, FMBA, Arkhangelsk, Russia |

|

Ratnikova I. Yu. |

City Polyclinic No. 1, Petrozavodsk, Russia |

|

Kosheleva I. P. |

City Polyclinic No. 3, Syktyvkar, Russia |

|

Volkova M. G., Yablokova A. V., Bessonova N. A. |

City Polyclinic No. 96, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Pavlenko S. S. |

Polyclinic of the Gurevsky Central District Hospital, Gurevsk, Russia |

|

Postol A. S., Koshevaya D. S., Ryzhikova T. N., Voronkina A. V. |

Federal Center for High Medical Technologies of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Kaliningrad, Russia |

|

Lvov V. E., Grotova A. V. |

Regional Clinical Hospital, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|

Ivochkina M. I. |

City Polyclinic No. 11 of Krasnodar of the Ministry of Health of Krasnodar Krai, Krasnodar, Russia |

|

Arzumanova N. K. |

City Polyclinic No. 13 of the city of Krasnodar of the Ministry of Health of the Krasnodar Krai, Krasnodar, Russia |

|

Gerasimenko I. A. |

LLC "Preobrazhenskaya Clinic", Krasnodar, Russia |

|

Budanova V. A., Kondratyeva O. V. |

Federal Center for Cardiovascular Surgery of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Astrakhan, Russia |

|

Ibragimova D. M. |

LLC "MedTest", Akhtubinsk, Russia |

|

Saprykina E. E. |

Clinical Polyclinic No. 28 Volgograd, Russia |

|

Vrublevskaya N. S., Budanova O. V. |

Clinical Hospital "Rzhd-Meditsina" of the City of Rostov-On-Don", Rostov-On-Don, Russia |

|

Minosyan L. V. |

Medical and Sanitary Unit of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation for the Rostov Region", Rostov-on-Don, Russia |

|

Spitsina T. Yu., Gulova O. A., Longus K. A., Kartamysheva E. D., Uskova V. A. |

Volgograd Regional Clinical Cardiology Center, Volgograd, Russia |

|

Dyakonova A. G., Kalacheva N. M. |

City Polyclinic No. 1 of Rostov-on-Don, Rostov-on-Don, Russia |

|

Krechunova T. N. |

City Polyclinic No. 15 of the city of Krasnodar of the Ministry of Health of the Krasnodar Krai, Krasnodar, Russia |

|

Kartashova I. V., Kostrykina S. V., Rumbesht V. V. |

Clinical and diagnostic center "Health" of the city of Rostov-on-Don", Rostov-on-Don, Russia |

|

Stepanova M. I., Kolodina M. V. |

S.V. Ochapovsky Research Institute — Regional Clinical Hospital No. 1 of Ministry of Health of Krasnodar Krai, Polyclinic of the Center of Thoracic Surgery, Krasnodar, Russia |

|

Kiseleva M. A., Priymak I. V., Imamutdinov A. F., Komarova O. A. |

Regional Cardiology Dispensary, Astrakhan, Russia |

|

Shimonenko S. E., Simonova A. V., Vlasenko A. O., Babaeva A. V., Selezneva A. A. |

Regional clinical cardiology dispensary, Stavropol, Russia |

|

Gorbunova S. I. |

LLC "MRT-Expert Maykop", Stavropol, Russia |

|

Ismailova A. A., Gamzaeva D. M. |

Republican clinical hospital of emergency medical care, Makhachkala, Russia |

|

Goltyapin D. B., Aleynik O. N., Shcheglova E. V. |

LLC "Heart Department", Stavropol, Russia |

|

Murtilova A. A. |

Polyclinic No. 3, Makhachkala, Russia |

|

Totushev M. U., Asadulaeva G. Kh., Kurbanova I. M. |

Republican cardiology dispensary, Makhachkala, Russia |

|

Kotsoeva O. T. |

North Caucasus Multidisciplinary Medical Center of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Beslan, Russia |

|

Vinogradova N. G. |

City Clinical Hospital No. 38, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia |

|

Erofeeva S. G., Timoshchenko E. S., Nekrasov A. A. |

City Clinical Hospital No. 5, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia |

|

Kanysheva S. V., Egoshina N. E. |

Republican Clinical Hospital, Yoshkar-Ola, Russia |

|

Idiatullina V. R., Mindubaeva D. Yu. |

City Clinical Hospital No. 7, Kazan, Russia |

|

Safin D. D., Yakupova D. T., Ageeva G. Sh. |

Interregional Clinical Diagnostic Center, Kazan, Russia |

|

Skuratova M. A. |

N.I. Pirogov Samara City Clinical Hospital No. 1, Samara, Russia |

|

Zharkova S. M. |

LLC, Center of Modern Medical Technologies "Garantiya", Bor, Russia |

|

Malchikova S. V., Trushnikova N. S., Maksimchuk-Kolobova N. S. |

Kirov State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Kirov, Russia |

|

Grekhova L. V., Ivanova O. G., Filimonova I. A. |

Center for Cardiology and Neurology, Kirov, Russia |

|

Abseeva V. M., Galimova A. A., Gazimzyanova A. S., Opolonskaya P. E. |

Republican clinical and diagnostic center of the Ministry of Health of the Udmurt Republic, Izhevsk, Russia |

|

Baryshnikov A.G. |

Orenburg Regional Clinical Hospital, Orenburg, Russia |

|

Bizyaeva N.N., Ilinykh E. A. |

Clinical Cardiology Dispensary, Perm, Russia |

|

Begunova I.I., Shpakov A. V. |

LLC "Endosurgical Center", Kaluga, Russia |

|

Koziolova N. A. (Professor), Mironova S. V., Polyanskaya E. A., Chernyavina A. I. |

Perm Regional Clinical Hospital for War Veterans, Polyclinic, Perm, Russia |

|

Nadina I. S. |

Zubovo-Polyanskaya District Hospital, Polyclinic, Zubovo-Polyana, Russia |

|

Zasetskaya S. A., Idabaeva N. V. |

City Clinical Hospital No. 40, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia |

|

Amirova I. V. |

Samara City Polyclinic No. 3, Clinical and Diagnostic Department, Samara, Russia |

|

Gubareva I. V., Tyurina I. A., Gandzhaliev A. T. |

Clinical hospital "RZhD-Medicine", Polyclinic, Samara, Russia |

|

Kuzmin V. P., Sosnova Yu. G., Tysyachnova A. S., Vasileva M. S. |

V.P. Polyakov Samara Regional Clinical Cardiology Dispensary, Samara, Russia |

|

Zhuravleva A. A., Ref E. Z. |

Samara city consultative and diagnostic polyclinic No. 14, Samara, Russia |

|

Ezhov A. V., Vasilev M. Yu., Odintsova N. F. |

City Clinical Hospital No. 9 of the Ministry of Health of the Udmurt Republic, polyclinic, Izhevsk, Russia |

|

Ionova T. S., Grayfer I. V. |

Regional Clinical Cardiology Dispensary, Saratov, Russia |

|

Nikulina E. A. |

Saratov City Polyclinic No. 16, Saratov, Russia |

|

Volodina E. N., Shevchenko E. A., Makarova T. A. |

N.N. Burdenko Penza Regional Clinical Hospital, Cardiology Dispensary at the Polyclinic, Penza, Russia |

|

Gubanova E. N., Sevastyanova E. A., Kulikova T. V. |

Regional Cardiology Dispensary, Ul’yanovsk, Russia |

|

Zubareva I. G., Kharasova A. F. |

Republican Cardiology Center, Ufa, Russia |

|

Yagushova N. I., Tsaregorodtseva V. V. |

Republican cardiology dispensary of the Ministry of Health of the Chuvash Republic, Cheboksary, Russia |

|

Bagrova S. L., Baraeva E. G., Kurganskaya A. A. |

City Polyclinic No. 4, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia |

|

Isaeva A. V., Kueyyar-Egorova O.-M. Kh., Grebneva I. Yu. |

Central City Hospital No. 20, Ekaterinburg, Russia |

|

Bykov A. N., Gorbunova N. A., Shakhmaeva N. B. |

Sverdlovsk Regional Clinical Hospital No. 1, Ekaterinburg, Russia |

|

Grachev V. G., Stepanova A. Yu. |

LLC "European Medical Center "UMMC-Health", Ekaterinburg, Russia |

|

Shimkevich A. M. |

LLC "Medical Center of Ultrasound Diagnostics Medar", Aramil, Russia |

|

Melnikova T. V. |

Tula City Hospital No. 13, Tula, Russia |

|

Mamedova S. I., Rakhmetova I. Yu., Melnikova E. A. |

District cardiology dispensary "Center for diagnostics and cardiovascular surgery", Surgut, Russia |

|

Kalinina V. A., Bakhmatova Yu. A., Antipina N. S. |

Tyumen Cardiology Research Center (branch of the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution "Tomsk National Research Medical Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences"), Tyumen, Russia |

|

Evsina M. G., Klochkova V. V., Devyatova M. D. |

Aramil City Hospital, Aramil, Russia |

|

Egorova A. N., Pospelova N. V. |

Central City Hospital No. 7, Polyclinic No. 3, Ekaterinburg, Russia |

|

Redkina M. V., Surovtseva I. V. |

Regional Clinical Hospital No. 3, Polyclinic No. 2, Chelyabinsk, Russia |

|

Oreshchuk G. V. |

City Clinical Hospital No. 11, Chelyabinsk, Chelyabinsk, Russia |

|

Sedova E. Yu. |

Clinical hospital "RZhD-Medicine" Chelyabinsk, Chelyabinsk, Russia |

|

Alekhina M. N. |

City Polyclinic No. 8, Tyumen, Russia |

|

Abakumova A. S. |

District Clinical Hospital, Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia |

|

Molodtseva E. Yu. |

City Clinical Hospital No. 5, Chelyabinsk, Russia |

|

Gorbacheva N. S., Shtark T. N. |

Regional Clinical Hospital, Barnaul, Russia |

|

Zenin S. A., Kononenko O. V., Fedoseenko A. V., Pyataeva O. V. |

Regional Cardiology Dispensary, Novosibirsk, Russia |

|

Rakhmonov S. S., Zarudneva N. Yu., Vyborova M. V. |

E.N. Meshalkin National Medical Research Center of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Novosibirsk, Russia |

|

Gass I. A., Natsarenus T. A. |

LLC "Multi-Disciplinary Center for Modern Medicine "Euromed", Omsk, Russia |

|

Ustyugov S. A., Khomchenko R. V., Marilovtseva O. V. |

Regional Clinical Hospital, Krasnoyarsk, Russia |

|

Cherepnina Yu. S. |

LLC "International Medical Center Medical On Group — Krasnoyarsk", Krasnoyarsk, Russia |

|

Bratishko I. A., Reshetnikova T. I., Savchenko M. V. |

Clinical cardiology dispensary, Omsk, Russia |

|

Zubakhina E. E. |

City Polyclinic No. 4, Omsk, Russia |

|

Sorokina E. A. |

Clinical Medical and Sanitary Unit No. 9, Omsk, Russia |

|

Nikulina S. Yu. (Professor), Chernova A. A., Shcherbakova V. E. |

I.S. Berzon Krasnoyarsk Interdistrict Clinical Hospital No. 20, Krasnoyarsk, Russia |

|

Veselovskaya N. G., Vorobyeva Yu. A., Kiseleva E. V. |

Altai Regional Cardiology Dispensary, Barnaul, Russia |

|

Ledeneva E. S. |

City Clinical Polyclinic No. 2, Novosibirsk, Russia |

|

Batekha V. I., Mankovskaya T. Sh. |

Regional Clinical Hospital, Irkutsk, Russia |

|

Panacheva E. P., Rozhnev V. V., Vasilyeva O. A. |

L.S. Barbarash Kuzbass Clinical Cardiology Dispensary, Kemerovo, Russia |

|

Mariich O. I., Terekhova A. Yu. |

City Clinical Hospital of Emergency Medical Care No. 2, Novosibirsk, Russia |

|

Tsygankova O. V. (Professor), Latyntseva L. D., Voevoda S. M., Timoshchenko O. V. |

Research Institute of Therapy and Preventive Medicine — branch of the Federal Research Center Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, Russia |

|

Lozhkina N. G. (Professor) |

LLC "Ersi Medical", Novosibirsk, Russia |

|

Musurok T. P., Sosnina D. B.-N., Garkusha A. S. |

Primorsky Regional Clinical Hospital No. 1, Vladivostok, Russia |

|

Ermolaeva N. A., Lukyanchikova V. F. |

S.I. Sergeev Regional Clinical Hospital No. 1 of the Ministry of Healthcare of Khabarovsk Krai, Khabarovsk, Russia |

|

Zakharchuk N. V. |

LLC "PrimaMed+", Vladivostok, Russia |

|

Dyakova E. A., Pomogalova O. G. |

Vladivostok Clinical Hospital No. 1, Vladivostok, Russia |

|

Nikitina M. V., Panchenko E. A. |

Regional Clinical Hospital No. 2, Vladivostok, Russia |

|

Trenina E. V. |

Clinical and Diagnostic Center of the Ministry of Healthcare of Khabarovsk Krai, Khabarovsk, Russia |

|

Garmaeva O. V. |

Clinical hospital "RZhD-Medicine" of the city of Ulan-Ude, Ulan-Ude, Russia |

|

Khusainova N. M., Sodnomova L. B., Sultimova I. S. |

N.A. Semashko Republican Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Buryatia, Ulan-Ude, Russia |

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1

STROBE Statement Checklist

|

Item No |

Recommendation |

||

|

Title and abstract |

1 |

(a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract |

+ |

|

(b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found |

+ |

||

|

Introduction |

|||

|

Background/rationale |

2 |

Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported |

+ |

|

Objectives |

3 |

State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses |

+ |

|

Methods |

|||

|

Study design |

4 |

Present key elements of study design early in the paper |

+ |

|

Setting |

5 |

Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection |

+ |

|

Participants |

6 |

(a) Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants. Describe methods of follow-up |

+ |

|

(b) For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed |

NA |

||

|

Variables |

7 |

Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable |

+ |

|

Data sources/measurement |

8* |

For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group |

+ |

|

Bias |

9 |

Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias |

+ |

|

Study size |

10 |

Explain how the study size was arrived at |

+ |

|

Quantitative variables |

11 |

Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why |

+ |

|

Statistical methods |

12 |

(a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding |

+ |

|

(b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions |

NA |

||

|

(c) Explain how missing data were addressed |

+ |

||

|

(d) If applicable, explain how loss to follow-up was addressed |

+ |

||

|

(e) Describe any sensitivity analyses |

NA |

||

|

Results |

|||

|

Participants |

13* |

(a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study — e.g., numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed |

+ |

|

(b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage |

+ |

||

|

(c) Consider use of a flow diagram |

+ |

||

|

Descriptive data |

14* |

(a) Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders |

+ |

|

(b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest |

+ |

||

|

(c) Summarize follow-up time (e.g., average and total amount) |

+ |

||

|

Outcome data |

15* |

Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time |

+ |

|

Main results |

16 |

(a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included |

+ |

|

(b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized |

+ |

||

|

(c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period |

NA |

||

|

Other analyses |

17 |

Report other analyses done — e.g., analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses |

NA |

|

Discussion |

|||

|

Key results |

18 |

Summarize key results with reference to study objectives |

+ |

|

Limitations |

19 |

Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias |

+ |

|

Interpretation |

20 |

Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence |

+ |

|

Generalisability |

21 |

Discuss the generalisability (external validity) of the study results |

+ |

|

Other information |

|||

|

Funding |

22 |

Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based |

+ |

Note: * — Provide information separately for exposed and unexposed groups. NA — not applicable.

Supplemental Figure 1. Patient disposition.

Abbreviations: IC — informed consent, EF — ejection fraction, HF — heart failure.

References

1. Jalloh MB, Averbuch T, Kulkarni P, et al. Bridging Treatment Implementation Gaps in Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Focus Seminar 2/3. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(6):544-58. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.050.

2. Lam CSP, Harding E, Bains M, et al. Identification of urgent gaps in public and policymaker knowledge of heart failure: Results of a global survey. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:1023. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-15405-4.

3. Shlyakhto EV, Zvartau NE, Villevalde SV, et al. Assessment of prevalence and monitoring of outcomes in patients with heart failure in Russia. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2020;25(12):4204. (In Russ.) doi:10.15829/1560-4071-2020-4204.

4. Khan MS, Shahid I, Bennis A, et al. Global epidemiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21:717-34. doi:10.1038/s41569-024-01046-6.

5. Bozkurt B. Concerning Trends of Rising Heart Failure Mortality Rates. JACC Heart Fail. 2024;12:970-2. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2024.04.001.

6. Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. A Systematic Review and Network MetaAnalysis of Pharmacological Treatment of Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2022;10:73-84. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2021.09.004.

7. Glynn P, Lloyd-Jones DM, Feinstein MJ, et al. Disparities in Cardiovascular Mortality Related to Heart Failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2354-5. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.042.

8. Sayed A, Abramov D, Fonarow GC, et al. Reversals in the Decline of Heart Failure Mortality in the US, 1999 to 2021. JAMA Cardiol. 2024;9:585-9. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2024.0615.

9. Seferović PM, Vardas P, Jankowska EA, et al. The Heart Failure Association Atlas: Heart Failure Epidemiology and Management Statistics 2019. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:90614. doi:10.1002/ejhf.2143.

10. Foroutan F, Rayner DG, Ross HJ, et al. Global Comparison of Readmission Rates for Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:430-44. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.040.

11. Tromp J, Bamadhaj S, Cleland JGF, et al. Post-discharge prognosis of patients admitted to hospital for heart failure by world region, and national level of income and income disparity (REPORT-HF): a cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8: e411-e422. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30004-8.

12. Crespo-Leiro MG, Anker SD, Maggioni AP, et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:613-25. doi:10.1002/ejhf.566.

13. Jones NR, Roalfe AK, Adoki I, et al. Survival of patients with chronic heart failure in the community: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1306-25. doi:10.1002/ejhf.1594.

14. Ferreira JP, Girerd N, Rossignol P, Zannad F. Geographic differences in heart failure trials. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:893-905. doi:10.1002/ejhf.326.

15. Ang N, Chandramouli C, Yiu K, et al. Heart Failure and Multimorbidity in Asia. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2023;20:24-32. doi:10.1007/s11897-023-00585-2.

16. Polyakov DS, Fomin IV, Belenkov YN, et al. Chronic heart failure in the Russian Federation: what has changed over 20 years of follow-up? Results of the EPOCH-CHF study. Kardiologiia. 2021;61(4):4-14. (In Russ.) doi:10.18087/cardio.2021.4.n1628.

17. Gilyarevsky SR, Gavrilov DV, Gusev AV. Retrospective analysis of electronic health records of patients with heart failure: the first Russian experience. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2021;26(5):4502. (In Russ.) doi:10.15829/1560-4071-2021-4502.

18. Soloveva AE, Medvedev AE, Lubkovsky AV, et al. Total, age and sex-specific mortality after discharge of patients with heart failure: the first large-scale cohort realworld study on Russian population. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2024;29(6):5940. (In Russ.) doi:10.15829/1560-4071-2024-5940. EDN: CTTQTF.

19. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-7. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010.

20. Shlyakhto Е, Belenkov YN, Boytsov S, et al. Prospective observational multicenter registry study of patients with chronic heart failure in the Russian Federation (PRIORITY-CHF): rationale, objectives and study design. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2023;28(10):5593. (In Russ.) doi:10.15829/1560-4071-2023-5593. EDN: AMDHTV.

21. Russian Society of Cardiology. 2020 Clinical practice guidelines for Chronic heart failure. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2020;25(11):4083. (In Russ.) doi:10.15829/1560-4071-2020-4083.

22. Savarese G, Stolfo D, Sinagra G, Lund LH. Heart failure with mid-range or mildly reduced ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:100-16. doi:10.1038/s41569021-00605-5.

23. G-CHF Investigators, Joseph P, Roy A, et al. Global Variations in Heart Failure Etiology, Management, and Outcomes. JAMA. 2023;329:1650-61. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5942.

24. Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, et al. Medical Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: The CHAMP-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:351-66. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.070.

25. Rakisheva A, Soloveva A, Shchendrygina A, Giverts I. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Frailty: From Young to Superaged Coexisting HFpEF and Frailty. Int J Heart Fail. 2024;6:93-106. doi:10.36628/ijhf.2023.0064.

26. Schaufelberger M, Basic C. Increasing incidence of heart failure among young adults: how can we stop it? Eur Heart J. 2023;44:393-5. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac730.

27. Shlyakhto EV. Classification of heart failure: focus on prevention. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2023;28(1):5351. (In Russ.) doi:10.15829/1560-4071-2023-5351. EDN: RVHDCY.

28. Bayes-Genis A, Bozkurt B. Pre-Heart Failure, Heart Stress, and Subclinical Heart Failure: Bridging Heart Health and Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2024;12:1115-8. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2024.03.008.

29. Pfeffer MA, Shah AM, Borlaug BA. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction In Perspective. Circulation Research. 2019;124:1598-617. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313572.

30. Kapelios CJ, Shahim B, Lund LH, Savarese G. Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics and Cause-specific Outcomes in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Card Fail Rev. 2023;9: e14. doi:10.15420/cfr.2023.03.

31. Lopatin YM, Nedogoda SV, Arkhipov MV, et al. Pharmacoepidemiological analysis of routine management of heart failure patients in the Russian Federation. Part I. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2021;26(4):4368. (In Russ.) doi:10.15829/1560-4071-2021-4368.

32. Bayes-Genis A, Coats AJS. "Peptide for Life" in primary care: work in progress. Eur Heart J. 2021: ehab829. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab829.

33. Roalfe AK, Lay-Flurrie SL, Ordóñez-Mena JM, et al. Long term trends in natriuretic peptide testing for heart failure in UK primary care: a cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2021;43:881-91. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab781.

34. Johansen ND, Vaduganathan M, Zahir D, et al. A Composite Score Summarizing Use and Dosing of Evidence-Based Medical Therapies in Heart Failure: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Circ Heart Fail. 2023;16: e009729. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.122.009729.

35. Stolfo D, Lund LH, Benson L, et al. Persistent High Burden of Heart Failure Across the Ejection Fraction Spectrum in a Nationwide Setting. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11: e026708. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.026708.

36. Teng THK, Tromp J, Tay WT, et al. Prescribing patterns of evidence-based heart failure pharmacotherapy and outcomes in the ASIAN-HF registry: a cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6: e1008-e1018. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30306-1.

37. Bozkurt B, Savarese G, Adamsson Eryd S, et al. Mortality, Outcomes, Costs, and Use of Medicines Following a First Heart Failure Hospitalization: EVOLUTION HF. JACC Heart Fail. 2023;11:1320-32. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2023.04.017.

38. Van Spall HGC, Fonarow GC, Mamas MA. Underutilization of Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy in Heart Failure: Can Digital Health Technologies PROMPT Change? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:2214-8. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.03.351.

39. Modin D, Lassen MCH, Claggett B, et al. Influenza vaccination and cardiovascular events in patients with ischaemic heart disease and heart failure: A meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:1685-92. doi:10.1002/ejhf.2945.

40. MacDonald MR, Tay WT, Teng THK, et al. Regional Variation of Mortality in Heart Failure With Reduced and Preserved Ejection Fraction Across Asia: Outcomes in the ASIAN-HF Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9: e012199. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.012199.

41. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Claggett B, et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1089-98. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2206286.

42. Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1383-92. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1313731.

43. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1451-61. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2107038.

44. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Assmann SF, et al. Regional Variation in Patients and Outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) Trial. Circulation. 2015;131:34-42. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013255.

45. Campbell RT, McMurray JJV. Comorbidities and differential diagnosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Clin. 2014;10:481-501. doi:10.1016/j. hfc.2014.04.009.